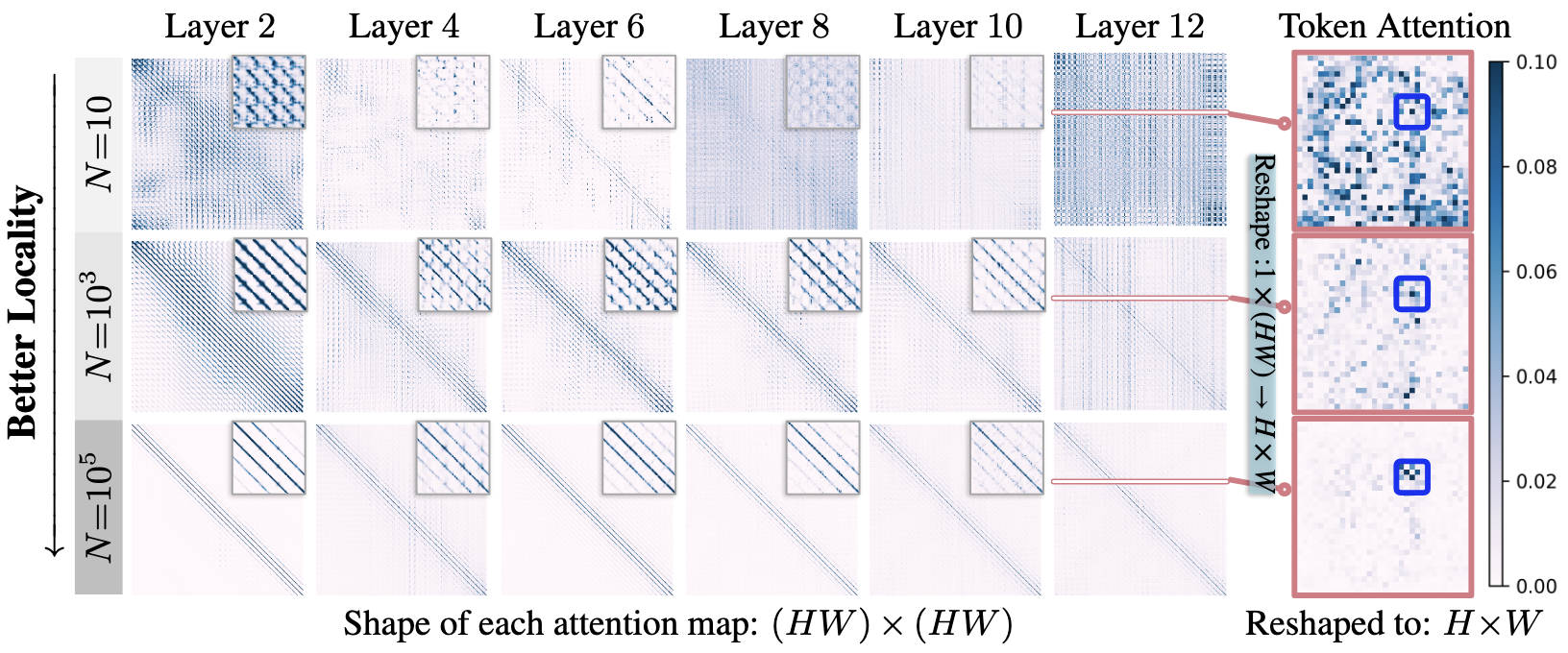

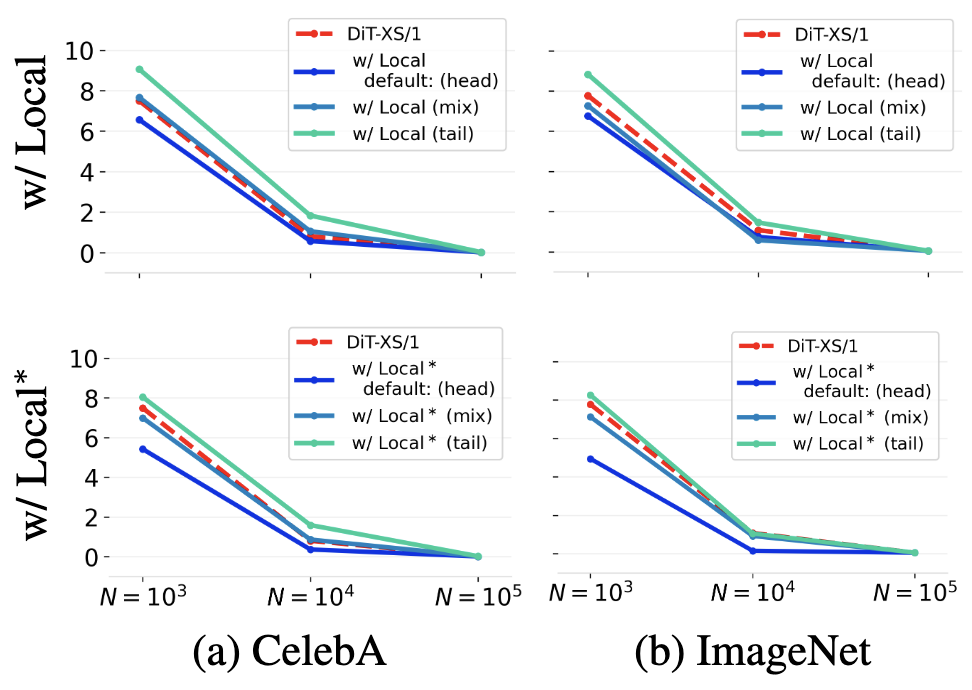

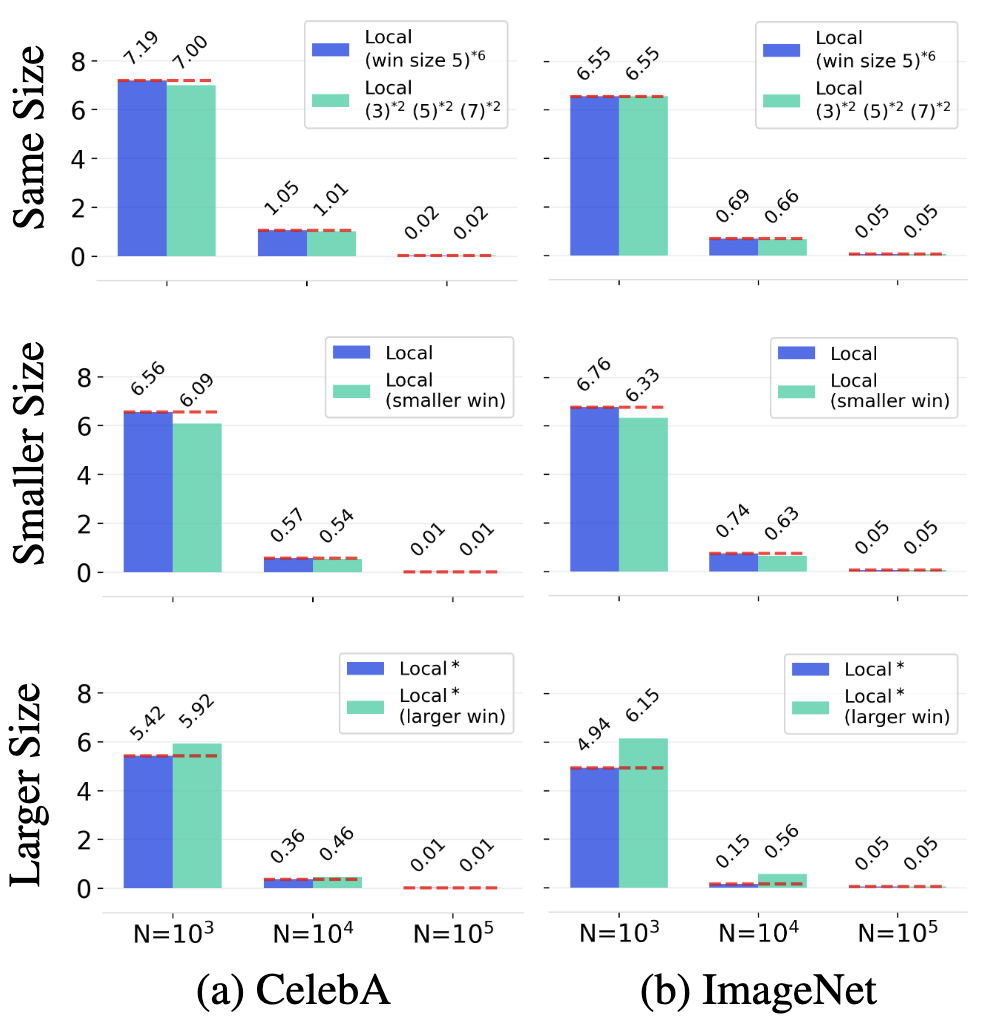

Applying Local Attentions to a DiT

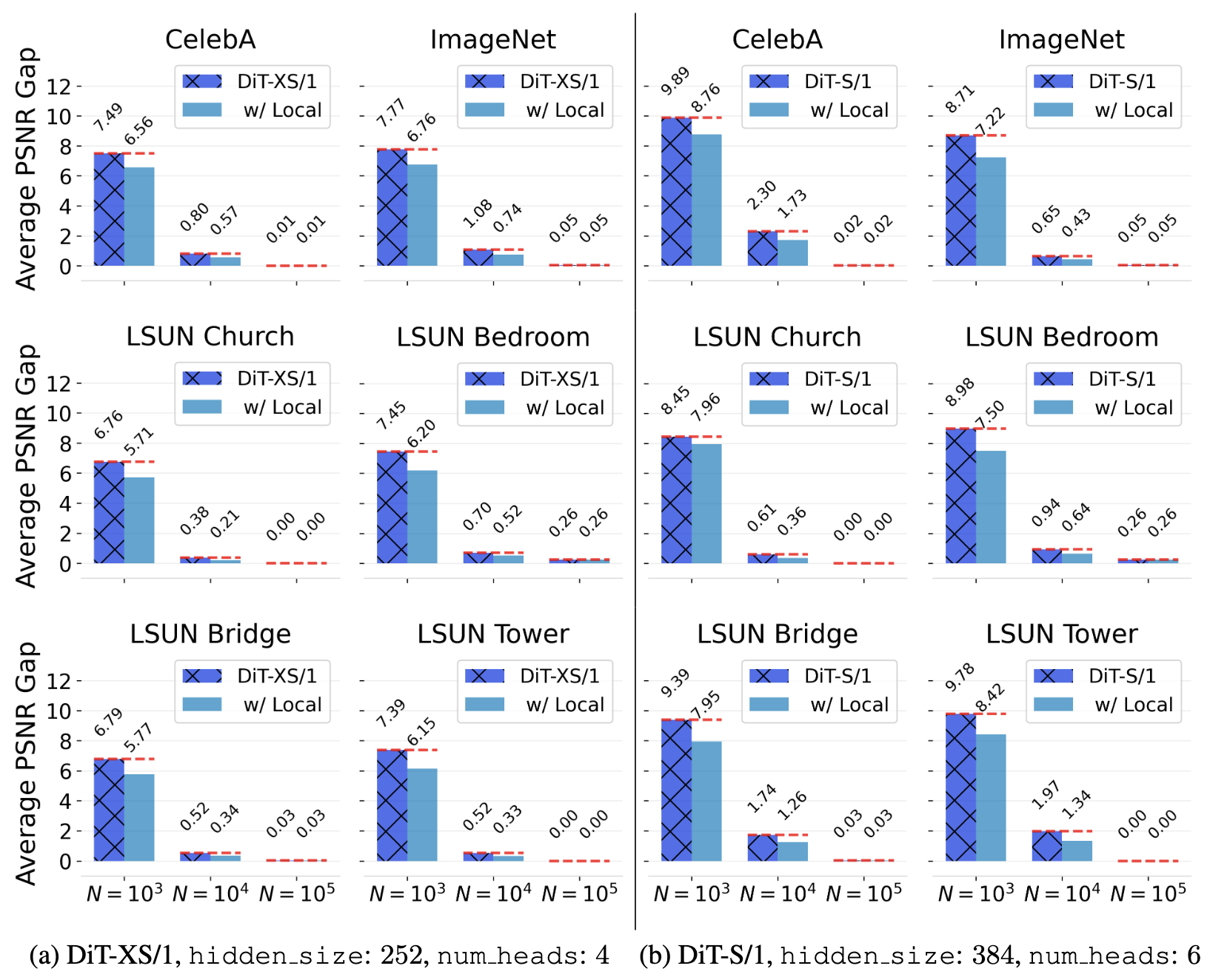

Using local attentions in a DiT can consistently improve its generalization (measured by PSNR gap) across different datasets and model sizes.

The above figure shows the PSNR gap$\downarrow$ comparison between a standard DiT and a DiT equipped with local attention for two architectures: (a) DiT-XS/1 and (b) DiT-S/1. Incorporating local attention reduces the PSNR gap consistently across $N{=}10^3$, $N{=}10^4$, and $N{=}10^5$. This advantage is robust across six different datasets and both DiT backbones. In this setup, local attention with window sizes $\left(3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13\right)$ is applied to the first six layers of the DiT. Textured bars highlight the default DiT baselines.